Has Utah Skiing Reached Its Breaking Point?

Severe overcrowding and high-profile operational crises—such as the Park City ski patrol strike pictured above—have left many vacationers wondering whether Utah skiing and riding is worth it anymore.

When it comes to top-tier powder and stunning alpine terrain, few places have been more of a magnet for skiers and riders than the state of Utah. But over the past few years, the state has seen an explosive surge in visitation, which has reshaped the ski scene as we know it. But while multiple factors have made Utah’s ski resorts more accessible, they’ve also exposed a painful irony: the more people who flock to Utah, the harder it becomes to enjoy the slopes.

This raises the question: has the surge in popularity created an unsustainable experience?

In this article, we’ll go through the details behind Utah’s visitation spikes—and the associated infrastructure strain, operational controversies, and labor unrest that have followed in its wake.

The growth of Salt Lake City has been a huge contributor to the rising visitation at Utah’s ski resorts.

Popularity Surge

So just how big has this surge in popularity been?

Over the past five years, Utah's ski industry has experienced a significant rise in visitation, reflecting a growing interest in the state's renowned winter sports. During the 2021-2022 season, Utah's 15 resorts collectively reported 5.8 million skier visits, surpassing the previous record of 5.3 million visits in the 2020-2021 season.

This upward trend continued into the 2022-2023 season, which saw a remarkable 7.1 million skier visits—a 22% increase from the prior season and the highest in the state's history. Although the 2023-2024 season experienced a slight decline to approximately 6.75 million skier visits, it still ranks as the second-highest on record, indicating sustained interest in Utah's ski offerings. Over the past five years, Utah's ski industry has achieved an overall average visitation increase of 32%, underscoring the state's growing appeal as a destination for skiing and riding.

Over the past five seasons, Utah’s ski industry has grown by a staggering 32%. Visitation numbers in the above graph are rounded to the nearest 100,000.

NOTE: The 2019-20 season was cut short due to COVID-19.

A huge contributor to this trend in visitation—and more broadly, the population dynamics in these areas—has been the rise of remote work. Salt Lake City, for instance, experienced a 14% population increase from 2010 to 2020, positioning it among the fastest-growing cities in the United States. The prevalence of remote work in the Salt Lake City metropolitan area is notable, with 18.5% of the workforce operating remotely in 2023, surpassing the national average of 13.8%.

When it comes to Park City, the raw number of residents actually hasn’t increased. But that doesn’t tell the full story. In Park City, the influx of remote workers and new residents has contributed to a booming real estate market, which has priced many historical residents out. The median home price in Park City reached approximately $4 million in 2024, more than double the 2019 figure, reflecting the growing demand for housing in proximity to the town’s outdoor amenities. While still much cheaper than Park City, similar trends occurred in the closeby towns of Heber City and Kamas.

The Epic and Ikon Passes have driven millions of visitors to Utah’s ski resorts—with the unlimited-access Park City and Solitude seeing especially high demand.

Epic and Ikon Passes

A big factor that has enabled both the large transplant population and vacation crowd to visit Utah’s ski resorts more frequently: the introduction of the Epic and Ikon Passes. These multi-resort mega passes have made the state’s best ski resorts more accessible than ever—but not without significant challenges. In large part thanks to their weeklong or unlimited access policies, these multi-resort passes have driven record-breaking visitation—and while this might be a good thing on the surface, the demand has been so high that resorts have not been able to properly handle it.

The surge in visitation driven by the Epic and Ikon Passes has hit some resorts harder than others. In Utah, Park City and Solitude have faced especially intense pressures as the sole "unlimited" options on their respective passes.

As the only Utah resort on the Epic Pass, Park City has become a lightning rod for visitation spikes. Its status as the largest ski area in the United States by skiable acreage—with 7,300 acres of terrain—makes it a natural draw for Epic Pass holders. However, this distinction has created immense strain. On peak days, parking lots fill before sunrise, lift lines can exceed 45 minutes, and the resort’s infrastructure struggles to keep pace with demand.

On the Ikon Pass side, Solitude faces a similar dilemma. While it’s nowhere near as big as Park City, Solitude has become a magnet for local Ikon skiers and riders due to its unlimited access on the full and Base Passes. In contrast, other Ikon resorts in the state—like Alta, Snowbird, Brighton, Snowbasin, and Deer Valley—limit passholders to seven days each, effectively funneling a higher proportion of day-to-day visitation to Solitude (in the cases of Alta, Snowbasin, and Deer Valley, there is no access at all on the Ikon Base Pass, and purchasers must upgrade to an Ikon full or Base Plus Pass to visit these mountains).

Hours-long backups along the access highways to Utah’s ski resorts have become frequent occurrences in recent years.

Traffic Issues and Parking Policies

But while Park City and Solitude have arguably been impacted the most, the vast majority of the other Epic and Ikon mountains are still feeling the heat of the visitation interest. And rather than leaving or restricting access on these passes, most—albeit not all—of these resorts have added new less-than-user-friendly policies to manage the influx of skiers and snowboarders.

The Cottonwood Canyons—home to Alta, Snowbird, Brighton, and Solitude—are ground zero for Utah's ski traffic issues. On powder days, the narrow Big and Cottonwood Canyon roads transform into gridlocked highways, with miles-long backups of hopeful skiers and riders a common occurrence. The Cottonwoods are home to some of the snowiest terrain in the world, and snowstorms often exacerbate the problem, creating dangerous driving conditions that make the roads prone to accidents and result in highway closures. For many, the commute to these resorts has become just as challenging as the skiing and riding itself.

So what’s been done to solve these problems? Well, over the past five years, resorts and local authorities have introduced several measures to address the gridlock—but notably, none of them have involved limiting multi-resort pass sales.

Alta, Snowbird, Solitude, and Brighton have all rolled out paid parking systems requiring advance reservations. Park City has done something similar on all of its Park City Mountain-side lots, with the town of Park City suffering from similar congestion problems to the Cottonwoods despite easier-to-drive roads. Utah’s Powder Mountain has also rolled out its own set of new parking policies, but that resort’s recent changes have been so wild and so specific to that one mountain that we’re saving our thoughts for a dedicated video.

At Alta, Solitude, and Brighton, no free parking is available when their reservation policies are in effect, while at Snowbird and Park City, there’s a mix of reserved and first-come, first-served parking. These systems are designed to reduce vehicle counts and encourage carpooling—and they have succeeded in easing congestion on peak days. Parking prices range from $10 to $25, with discounts for cars carrying three or more people. At most of these resorts, carpools of 4 or more people have been able to park for free, although at some resorts, this has recently increased from a complimentary parking policy for 3 or more people in past years.

While this approach has helped control traffic, it comes with trade-offs. For locals accustomed to last-minute powder day decisions, the need to reserve parking in advance has made skiing and riding less spontaneous. Additionally, the added parking costs have increased the financial burden on skiers and riders who don’t carpool, making an already expensive sport even pricier.

Rather than limiting pass sales, many Utah ski resorts have artificially tempered demand with paid, reservation-based parking policies.

Incoherent Policies Across Different Resorts

Finally, a lack of cohesive parking policies has somewhat undermined the effectiveness of these efforts. In particular, the differing approaches of Alta and Snowbird, the two resorts with shared access via the Little Cottonwood Canyon access road, have created unintended consequences that arguably shoot one another in the foot.

Alta has adopted a strict paid parking reservation system on Fridays, weekends, and holidays. This approach aims to reduce traffic by requiring skiers to secure a spot in advance, eliminating the unpredictability of cars circling the canyon in search of last-minute openings. The system also incentivizes carpooling by offering lower rates for cars carrying three or more people, helping to align the resort’s parking policies with sustainability goals.

However, Alta’s policy effectiveness is undermined by Snowbird’s more flexible approach just down the road. Unlike Alta, Snowbird maintains a hybrid parking policy. While some lots require reservations or have carpool-only restrictions, others remain first-come, first-serve and are free of charge. On busy days, this partial availability of free parking often results in a significant number of last-minute visitors heading to Snowbird, especially on high-demand powder days.

Unfortunately, many of these last-minute visitors drive through Little Cottonwood Canyon without a clear plan, hoping to find a spot at Snowbird. When they can’t, they just create additional unwanted congestion in the canyon and reduce the effectiveness of Alta’s carefully structured reservation system. There are often signs at the bottom of the canyon when Snowbird’s unreserved parking fills up, but many drivers just go up and try to find a spot anyway.

That being said, there are some improvements this year. Starting with the 2024-25 season, enforcement of the traction law in the Cottonwood Canyons has become significantly stricter. On days with significant snow accumulation, police now stop vehicles at the canyon mouths to ensure compliance, requiring all cars to have chains installed or snow tires on all four wheels. Vehicles that fail to meet these standards are now turned away—with no exceptions. This represents a major shift from previous seasons, when enforcement was more sporadic.

Significant bus cuts since 2022 have left Utah skiers and riders without adequate public transportation options to several ski resorts.

Utah’s Public Transportation Crisis

So if the parking policies are so restrictive, why are so many people still driving to the resorts? Well, Utah’s public transportation services—which would ideally provide a desirable alternative to get to the resorts—have been facing a years-long crisis.

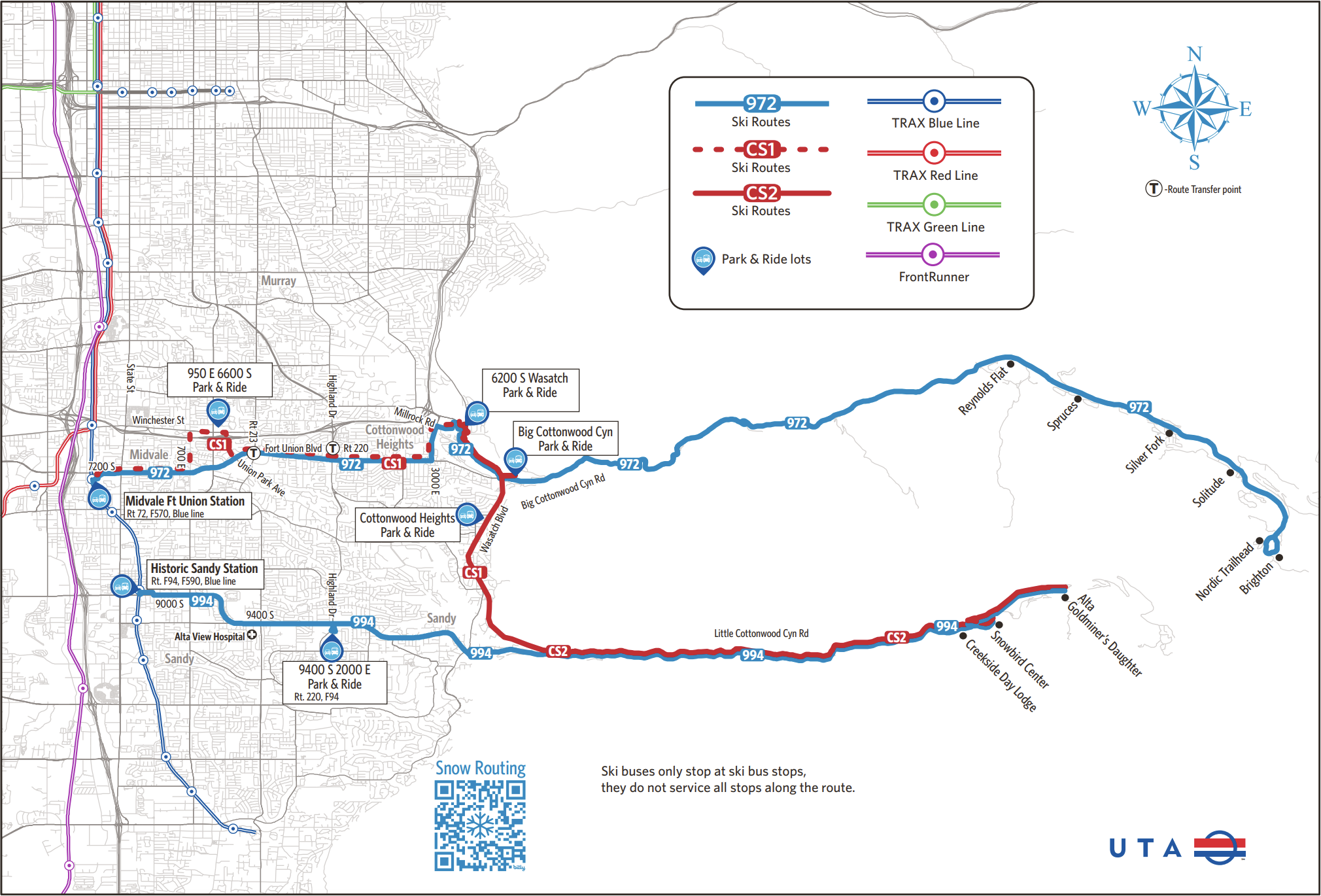

The Utah Transit Authority (UTA) implemented major cuts to ski bus services in 2022, citing driver shortages and budget constraints. These reductions drastically limited public transportation options for the Cottonwood Canyons and completely eliminated direct service from Salt Lake City to Park City.

The 2022 cuts gutted bus frequency and capacity for Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons, with routes operating fewer times per day and covering fewer stops. For example, the 953 ski bus route to Little Cottonwood Canyon was completely discontinued, while the 972 route to Big Cottonwood Canyon and the 994 route to Little Cottonwood Canyon were halved in frequency. The lack of accessible transit disproportionately impacted visitors without access to canyon parking and left car-free skiers with limited options for reaching the slopes.

In 2024, UTA partially restored services by introducing new routes to Little Cottonwood Canyon. These added routes increased frequency and capacity during peak times, providing some relief for visitors to Alta and Snowbird. However, even with the new routes, public transit to Little Cottonwood Canyon still falls short of pre-2022 levels.

While UTA has restored some bus service to Little Cottonwood Canyon since the 2022 cuts, Big Cottonwood Canyon has yet to see any service restoration.

Despite the improvements in Little Cottonwood Canyon, Big Cottonwood Canyon has yet to see any restoration of its lost transit services. Visitors to Solitude and Brighton remain without adequate public transportation options, forcing many to drive up the canyon. This poses a significant challenge, particularly for Solitude, which as we mentioned sees especially heavy visitation due to its unlimited access on the Ikon Pass. With canyon parking increasingly restricted and public transit lacking, Big Cottonwood Canyon visitors often face difficult choices between battling for space on a bus and navigating complex parking reservation systems.

The transit crisis extends beyond the Cottonwoods. No direct bus routes from Salt Lake City to Park City have been reinstated since the 2022 cuts, leaving many visitors to North America’s largest ski resort reliant on inefficient bus transfers or personal vehicles. This isn’t as big of a deal as the Cottonwoods bus cuts, as lots of Park City visitors stay directly in town rather than the Salt Lake area, but it doesn’t help Park City’s already strained infrastructure and persistent traffic issues.

The Visitation “Self-Regulation” Issue

The practical challenges of reaching the mountain—whether through traffic, parking costs, or limited transit options—mean that visitation effectively self-regulates. With inadequate public transit options and increasingly cash-grabby parking policies, these measures effectively deter skiers and riders—especially those without large wallets—without explicitly capping numbers through pass restrictions.

This strategy is most evident in Solitude’s recent removal of blackout dates for Ikon Base Pass holders. While this change technically grants unrestricted access during holidays, the reality is that few visitors can take advantage of it due to logistical hurdles. The lack of restored bus service means visitors must rely on personal cars, and Solitude’s expensive, reservation-based parking system further complicates access. For some, it’s a stark reminder that while passes may seem inclusive on paper, the realities of access tell a different story.

An inset of Park City’s trail map, with the cancelled Silverlode eight-pack highlighted in light red, and the cancelled Eagle six-pack highlighted in dark red.

The Park City Catastrophe

But while the Cottonwoods have faced their fair share of hardships over the past few years, they are nothing compared to the myriad of issues compounding at Park City. Under Vail Resorts' ownership, Park City has faced significant challenges in recent years, including disputes with local authorities, cancelled lift projects, and labor unrest among ski patrol staff.

Park City Lift Cancellations

In 2022, Park City planned to upgrade its lift infrastructure by replacing the Silverlode lift with an eight-person chair—which would have been the first of its kind in Vail Resorts' North American operations—and both the Eagle and Eaglet triple lifts with a new six-person chair. These upgrades aimed to alleviate congestion and improve the skier experience on the Park City side of the resort. However, the Park City Planning Commission halted these projects, citing concerns over increased demand into town from the higher lift capacity. As a result, the planned lift installations were cancelled for the 2022-23 season.

By the time the commission paused approval, key lift components had already been shipped to Park City, highlighting the unprecedented nature of their cancellation. In a telling move, the parts for the new lifts were shipped north to Whistler Blackcomb, where they have now been installed as replacements for other lifts.

These cancellations have left some notable issues on the mountain, especially with regard to crowd flow. The Eaglet triple chair had already been removed in anticipation of its replacement, leaving the medium-sized terrain park area it served with no dedicated chairlift service. While this lift never attracted a huge crowd, skiers and snowboarders now have to rely on the Crescent and King Con lifts to access this zone, creating inefficiencies and adding more strain on those specific lifts. Meanwhile, the overcrowding issues that the Silverlode and Eagle upgrades were meant to address remain unresolved, as skiers and riders continue to face long waits during peak times.

The Town lift is the only chairlift that directly serves downtown Park City—and due to a lawsuit, its future may be in jeopardy.

Park City Town Lift Lawsuit

In addition, it now seems possible that one of Park City’s other lifts could be forced to shut down in the short-to-medium-term future. The future of Park City’s iconic Town Lift is under threat, as the owners of the land beneath its base are currently suing Vail Resorts to terminate their lease. The lawsuit stems from a 2023 incident in which a skier was injured at the lift’s base area, with the owners alleging that Vail failed to meet contractual obligations to indemnify and defend them against liability claims. This dispute has added to the growing tensions between Vail and the local community, with the land owners signaling a desire to end their relationship with the company entirely.

Compounding the uncertainty, the current land-owning family recently listed the Town Lift Plaza property on sale for $27 million, raising questions about the lift’s future under new ownership. Vail Resorts has insisted it will continue operations as usual, citing its rights under the existing lease. However, the legal battle casts doubt on the long-term availability of the Town Lift, which doesn’t go all that fast or serve all that much terrain—but provides a very useful link between Main Street and the mountain that those staying downtown save tons of time from using.

Due to an unresolved wage dispute with Vail Resorts, the Park City Professional Ski Patrol Association unanimously voted to go on strike in December 2024.

Park City Ski Patrol Labor Dispute

But if you thought the tensions between Vail Resorts and Park City locals couldn’t get any worse after that, you probably haven’t been following the news. This issue of community trust has seriously come to a head over the past few weeks with an unresolved labor dispute between Park City’s ski patrol and Vail Resorts spiraling out of control.

Collapse of Initial Negotiations

The labor dispute has been years in the making, culminating in a strike that has put a spotlight on simmering tensions over wages, working conditions, and the broader relationship between employees and the resort operator. Negotiations began in earnest this past April when the last union contract expired, as the Park City Professional Ski Patrol Association (PCPSPA) pushed for higher wages to keep pace with the rising cost of living in Park City and the increased demands of their role. With housing costs in the area among the highest in the state and continuing to rise, many patrollers argued that their current pay made it unsustainable to live anywhere near the mountain they serve.

The union sought base pay raises from $21 an hour to $23 an hour, pointing to Vail Resorts’ record-setting revenues in recent years as evidence that the company could afford better compensation. The union also asked for improvements to benefits, including a health care stipend that would allow patrollers to stay on the same insurance policy year round, as well as additional hours flexibility and holiday pay.

Vail countered that it had already raised patrol wages by over 50% in the past four seasons, with the average pay exceeding $25 an hour, and offered an additional 4% wage increase for the 2024-25 season alongside a $1,600 equipment allowance. However, this wage increase would have been half of what the patrollers requested, and union leaders argued that this offer fell short of what was needed to attract and retain qualified patrollers—especially on one of the country’s largest, busiest, and still-growing ski mountains.

By December 2024, with negotiations stalled and tensions running high, the union voted unanimously to strike. The strike has spilled into Park City’s base areas, where striking ski patrollers have organized picket lines to bring attention to their cause.

Vail Resorts’ Temporary “Solution”

To keep operations running, Vail has leaned on patrollers from its other resorts, shipping in staff from across the country to cover essential safety duties at Park City. This approach has raised eyebrows among locals and some visitors, who question whether imported staff can adequately handle the unique challenges of Park City’s vast and complex terrain—especially in a position so critical to safety.

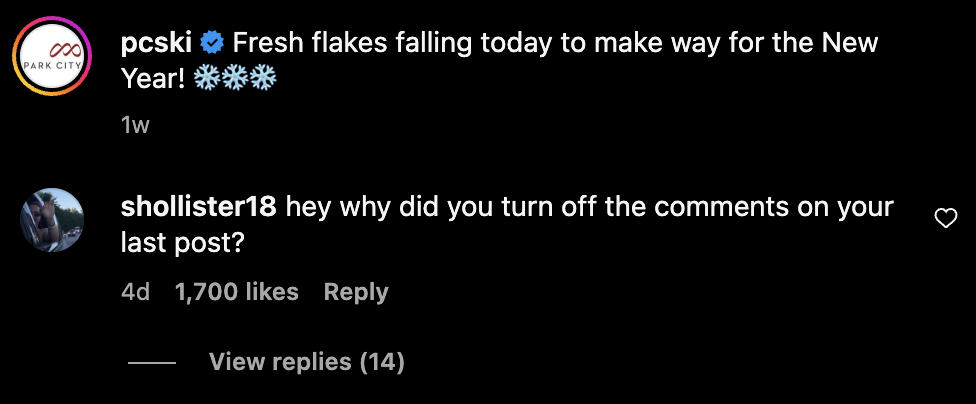

Park City released a video on Instagram discussing their operational issues with the ongoing ski patrol strike, but they turned off comments.

However, they didn’t turn off comments on their other posts.

Park City’s Operational Struggles and Blowback

The situation has been changing rapidly over the last few days, but a couple of things have become clear.

First off, Park City is lagging behind its competitors in terms of ability to get terrain open, with only around 29% of its trails open as of January 4. Park City says that a below-average winter has been a significant factor in the slow-roll of terrain openings—and it is true that Utah hasn’t had its best season so far—but with nearby Deer Valley seeing very similar snow conditions and already having over half of its footprint open, several questions have been raised about how much the strike and lack of experienced patrollers has played a role here.

It’s also telling that in recent days, Park City actually removed the trail percentage indicator on its website, indicating that Vail Resorts is feeling the heat from the situation at hand unfolding (the indicator has been removed from all Vail Resorts-owned mountains, likely because they all share the same website backend). However, guests can still see the raw number of trails open, so if this change happens to be damage control, it seems to be a pretty shortsighted attempt at it.

Another thing that has made it clear that Park City’s management is feeling the heat: a video response from Park City Mountain VP and COO Deirdra Walsh addressing the situation. In the video, she acknowledges that the strike has impacted the resort’s ability to get terrain on the Canyons side open. But notably, comments on that video are turned off, so Park City and Vail Resorts seem to be aware that they are losing the PR war right now. It’s also worth noting that Walsh also sent an internal email to Park City staff stating essentially the same thing.

Finally, with the strike now extending over a week in length, customer testimonials have started to roll in over the past few days—and they have not been good. Some customers have claimed that they’ve had to step in to help injured skiers due to unacceptable response times, and that even in certain cases when patrol has arrived, they’ve come solo and without adequate transportation equipment down the mountain. While we do not have concrete proof of these claims—or, if true, just how out of the ordinary they actually are, their widely publicized nature on both traditional and social media channels is the last thing Vail Resorts needs right now.

Vail Resorts (Stock: MTN) revenue growth has stagnated over the past year, and they’ve been reluctant to take on any additional expenses in recent months.

Why Is a $2 Per Hour Raise Such a Sticking Point for Vail Resorts?

Vail Resorts still turned a net profit of $230 million in FY ‘24—so why are they being so nitpicky over a raise that would cut into less than half of one percent of that at most? Well, one could argue the labor dispute at Park City has been fueled not just by disagreements over compensation, but by Vail Resorts’ broader financial posture in a period of declining growth. The company’s refusal to meet the ski patrol union’s demands comes as Vail faces financial headwinds, with its once-rapid revenue growth beginning to flatten. While the company is still wildly profitable, Vail’s stock price has dipped over the past year, reflecting market concerns about slowing expansion and increasing operational challenges.

Presumably in order to make its financials look better, Vail Resorts appears reluctant to take on additional expenses of any sort. The company is tightening its belt across the board, with a slowdown in capital investments across its portfolio and significant layoffs pending at its corporate office. While the union’s unwillingness to budge so far reflects an argument for fair pay that considers both inflation and the risks of their job, Vail’s unwillingness to budge so far underscores a company-wide strategy focused on appeasing its shareholders.

The Long-Reaching Implications of the Park City Strike—No Matter the Outcome

A recently-leaked email from patrollers at other Vail Resorts-owned mountains suggests that depending on how Vail plays its cards, this issue could metastasize outside of Park City.

How Vail Resorts handles this dispute in the coming weeks could set a precedent not just for Park City, but for all its operations across North America. The stakes are high, as evidenced by a recently-leaked email revealing dissatisfaction among ski patrol unions at Breckenridge, Crested Butte, and Keystone, on top of Park City itself. These unions expressed frustration over Vail’s decision to pressure patrollers from other resorts to cross picket lines, as well as its focus on stock buybacks and cash dividends.

If Vail Resorts gives in on these negotiations and other patrollers demand similar wage increases, we could see their net profit cut down by 1, 3, or even 5%—which, given the way public companies work, is probably not something that shareholders will be happy with, but we can’t know for sure.

At least as of today, it seems that there’s some good news, and the Park City ski patrol union says that there has been significant progress towards reaching an agreement in recent hours. We really hope they do, because this whole fiasco has ruined a lot of people’s vacations so far—and there are probably thousands of people who feel like they just threw months of their savings down the drain at this point.

It is worth iterating just how unprecedented of a situation this strike is—with the patrollers at Park City being the first to walk off the job at a major ski resort in perhaps over five decades. Even if Vail Resorts and the ski patrol union reach an agreement this weekend, we can assure you that this story is not over, be it for the Park City community, ski patrol unions across the US, and Vail Resorts as a whole.

Final Thoughts

So while each specific mountain might be facing its own unique issues, the mounting challenges facing Utah’s ski resorts—overcrowding, traffic gridlock, transit cuts, labor disputes, and stalled infrastructure projects—are all symptoms of two broader circumstances reshaping the state: an increasing population and rising cost of living. Over the past few years, Utah has seen such an influx of wealthier residents and tourists that local workers, especially those who make Utah’s ski resorts run—from bus drivers to lifties to ski patrollers—have found it increasingly difficult to afford housing or basic necessities near their jobs.

The tension between rising demand and limited capacity is reflected in nearly every aspect of Utah skiing today. The Cottonwood Canyons traffic crisis, restrictive paid parking policies, and Park City’s labor and development disputes are all part of a larger struggle to adapt to a state transformed by growth. For many, Utah remains a bucket-list destination, but for locals and long-time winter sports goers, the increasing cost—both literal and figurative—of accessing the mountains is eroding the soul of what once made skiing in Utah feel so special. If these issues aren’t addressed, the so-called “Greatest Snow on Earth” may no longer be enough to sustain the ski culture that has defined this state for decades.

Considering a ski trip to Utah this winter? Check out our comprehensive Utah rankings, as well as our Alta, Snowbird, Park City, Deer Valley, Brighton, and Solitude mountain reviews. You can also check out our detailed analysis on Vail Resorts’ financial headwinds in video form below.