Why All Major Utah Ski Resorts Exist Within Just a Small Sliver of the State

For decades, Utah has been one of the most prominent ski resort destinations, not just in the United States, but in the world. The region is known for its top-tier snow, incredible terrain, and world-class mountain infrastructure.

But what might be surprising to know is that the overwhelming majority of Utah’s ski resorts—and all of its commonly-agreed-upon destination ski mountains, exist across just a small sliver of this massive state. Utah spans nearly 85,000 square miles and is quite mountainous, so why are the vast majority of its ski resorts within just an hour’s drive of one another?

In this piece, we’ll go through why Utah’s ski resorts have developed across such a small portion of its land, and what this means when you’re planning your next trip there.

A brief overview of Utah’s geography

When considering what parts of Utah may or may not be conducive to skiable terrain, it’s first helpful to understand the general topography of the state. And Utah is a diverse state geographically, consisting of vast deserts, prominent snowy mountains, and everything in between.

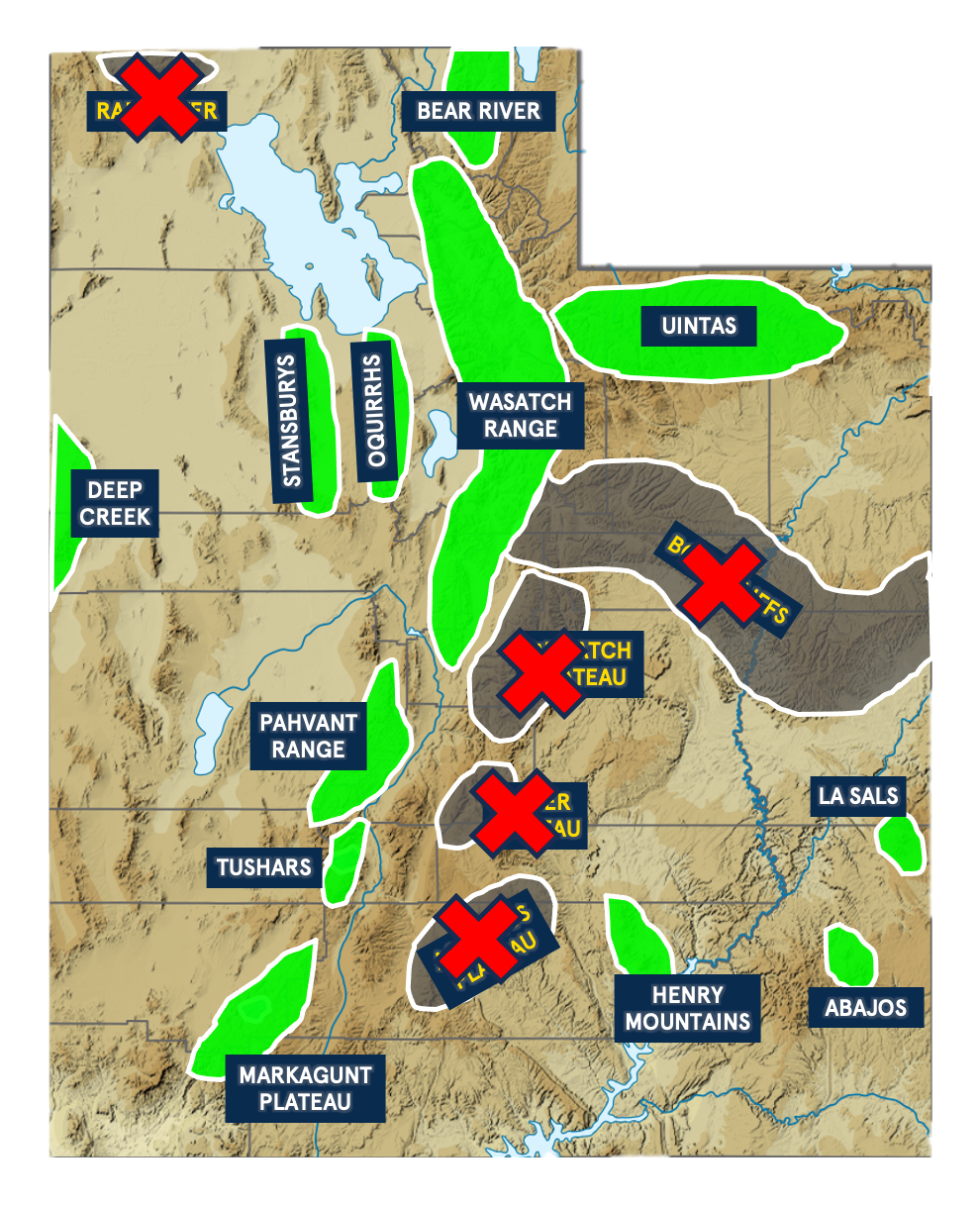

Here’s a map of Utah: all the areas highlighted in green have mountain ranges with notable elevation changes.

The main line of mountains runs through the middle of the state, with a couple of ranges that extend geographically horizontally through the east end of the state. The west end of the state is part of the Great Basin and much flatter, although there are a handful of prominent mountains at the extreme western end of the state. But despite this vast array of ranges, only a few of them hold conditions that truly make for practical ski resort operations—and even fewer offer the qualities needed to support the world-class fly-to destinations that most of you watching this video are probably interested in.

Reason #1: No Consistent Snowfall

The first circumstance that knocks out a bunch of these mountain ranges is the lack of snowfall. Utah is known for its self proclaimed greatest snow on earth, but some of its mountains barely get any snow at all. It’s worth noting that much of Utah is located in a barren desert, so even when it gets cold, there’s little moisture to carry snow into these mountains in the first place. While it’s rare that Utah’s mountains see absolutely zero snowfall, accumulation can be really scant—and dust on rocks is nowhere near enough to form a skiable base. This situation knocks out the Raft River Mountains, Book Cliffs, and most of the plateaus in the state.

Reason #2: Low Consistent Snowfall

Okay, so most of Utah’s other mountains do reliably see snow throughout the winter. So why aren’t many of them hospitable to ski resort development?

Well, even in some of the ranges where the accumulation sticks, it may just be at the tops of the mountains. As a result, the reliable snow line may not be low enough to support a prominent enough skiable descent needed for a workable ski resort. And even if the snow line is low enough to allow for decently long runs, the mountain’s prominence may start well below that snow line, making for difficult conditions to build a proper ski resort base and access road, and making it near impossible to ensure a reliable operating schedule. If you’ve been to a major ski resort in New Zealand, you know what we’re talking about.

Finally, in some cases where a mountain may have both a suitable base and enough snow-capped vertical to technically support a ski resort, the snow totals may just not be high enough to compete with the serious destinations. Ranges that get the axe from this category include the Henry Mountains, Pahvant Range, Deep Creek Range, La Sal Mountains, and even the southern part of the Wasatch Range south of Sundance.

It is worth noting that some of these ranges do offer suitable backcountry terrain, but if you do decide to explore these areas, make sure to go with a familiar guide and bring proper avalanche equipment with you.

Reason #3: Remoteness

Another large reason why many of Utah’s mountain ranges fall short for destination ski resort development: sheer remoteness.

While some of them might be able to support a resort snow-wise, several of these ranges are hours away from the nearest airport—or even town—and even if they offer sufficient snowfall and promising terrain, there’s very little infrastructure to allow people to conveniently get there. Perhaps even more importantly, there are very few activities besides the mountains themselves to incentivize people to go out of their way to visit. To put it another way, unlike Colorado, where every remote ski resort has an associated mountain town of at least some sort, these mountain ranges are incredibly sparsely populated.

Areas that fall short in feasibility based on this criteria include the Tushar Mountains and Abajo Mountains—and many of the ranges we mentioned earlier would doubly fail here as well. That said, the Tushar Mountains do actually call home to one ski resort—Eagle Point—but it’s small, does not extend up the entire mountain on which it’s located, and has very little going on outside the slopes. The Abajos also used to have a ski resort called Blue Mountain, but it was shuttered in the early 1990s due to its small, remote location. Like some of those we discussed earlier, both ranges mentioned here do offer suitable backcountry skiing and riding terrain—but good luck finding nearby accommodations.

The Abajo Mountains used to call home to a small ski resort, but limited tourism infrastructure made it financially infeasible past the early 1990s. Via: Steven Baltakatei Sandoval

Utah wilderness zones. Via: SUWA

Reason #4: Wilderness Protections

Approximately 12% of Utah’s land is protected for wilderness and recreational use. This status provides for undisturbed preservation of these lands, but it also means there’s pretty much no man-made development or industry allowed, including buildings, tree alterations, or even roads.

Naturally, ski resorts are big no-no’s in these protected areas.

This situation basically rules out one mountain range west of Salt Lake City: the Stansbury Mountains. While only about a third of the Stansburys exist in a wilderness area, the mountains that do are home to the range’s highest elevations and best snow, making the prospect of developing a ski resort there tough.

A couple of other sections of snow-laden mountain ranges, including the Uintas, Wasatch Range, and Bear River Range, are wilderness protected as well. Backcountry skiing is an option, but due to the lack of roads, access can be tough.

Deseret Peak’s Twin Couloirs may look like incredible skiing and riding terrain, but their wilderness status prohibits any development. Via: Derrell Williams

Reason #5: Terrain Layout

So now we’ve narrowed Utah’s mountain ranges down to only a couple, and most of these offer solid snow totals, skiable peaks, and sufficient nearby civilization. But there’s still a large chunk of mountainous terrain that does not make sense for serious ski destination development due to its topography.

Places such as the Uinta Mountains, Bear River Range, and Markagunt Plateau may be prominent overall, but at least in the parts that aren’t wilderness areas, they’re quite rolly, with much more mellow overall terrain than one might desire from a lift-served ski hill. There are some notably tough fall lines in these ranges, but they’re relatively short and come paired with lots of flat sections, making them less than practical locations to construct truly viable destination ski resorts.

It’s worth noting that all three of these ranges do or have had ski areas at some point, but the three that remain—Beaver Mountain and Cherry Peak in the Bear River Range and Brian Head on the Markagunt Plateau—are pretty small, especially when it comes to vertical descent. The Uinta Mountains were once home to a small ski hill called Grizzly Ridge, but it closed due to low visitation around 1990.

Ranges such as the Markagunt Plateau do host small ski areas, but the modest vertical descents make them tough sells for destination-goers.

Reason #6: Industrial Activity

So this just leaves two ranges left in the state—the Oquirrh Mountains and the Wasatch Range—and if you aren’t super familiar with Utah’s local hills, we probably haven’t even covered any resorts you’ve heard of yet. And of these two ranges, both of which border Salt Lake City, it turns out that the Oquirrhs are home to none of these resorts.

There are a couple of factors that hurt the Oquirrh Mountains as a home to ski resorts, including the fact that they’re just comparably less snowy and intense terrain-wise than the Wasatch Range, but the biggest one of all is that a substantial portion of this 30-mile mountain range is privately owned.

Yes, the Oquirrhs are home to one of the most substantial mining operations in North America—including the Bingham Canyon Mine, which is currently the deepest open-pit mine in the world—and a smelter complex at the far northern end of the range. A small fraction of the Oquirrhs are still open for development, but some of this land isn’t exactly desirable due to the nearby industrial complexes.

Plans did swirl to develop a ski resort within the range in the late 2000s—and the footprint would likely offer the snow, terrain, and available infrastructure to support it—but these plans never came to fruition, and the Oquirrhs remain backcountry-accessible only to this day.

A substantial industrial presence hurts the prospect of ski resort development in Utah’s Oquirrh Mountains.

Reason #7: Lake Effect Conditions

This leaves just one range, the Wasatch Mountains, as home to the overwhelming majority of Utah’s ski resorts—and perhaps every single destination that most of you reading this have heard of. And on top of all of the circumstances we already mentioned, there’s a huge geographical reason why Utah’s destination ski resorts are all concentrated within a small part of this mountain range: the exceptional climate.

The microregion’s proximity to the Great Salt Lake significantly influences the snowfall patterns in the region, resulting in lake effect snow. The lake effect—a meteorological phenomenon wherein cold air passes over a warmer lake—causes profoundly heavy snowfall along the Wasatch Range, precisely where the majority of ski resorts are situated.

But since the Great Salt Lake is so salinated, this accumulation is supremely dry and light, making for almost unbelievably effortless powder skiing. The consistency and quality of the snow are among the best not only in the state, but in all of North America, further enhancing the appeal of traveling from all over the world to ski or ride in this very small sliver of the state.

The Wasatch Range’s proximity to the Great Salt Lake results in exceptionally dry lake effect snow unmatched by any other destination ski region.

Reason #8: Salt Lake City

To make matters even more favorable for the Wasatch ski areas, the range also happens to be right next to Salt Lake City, by far the biggest metropolitan area in the state of Utah. Parts of this city are just 15 or so minutes from the closest ski resorts, and the furthest mountains are only a bit over an hour’s drive from the airport. This is way closer to any city than the vast majority of the other mountain ranges in the state—and even elsewhere in the country, it’s hard to find another city that’s this close to a substantial mountain range.

As far as we know, Salt Lake City’s proximity to this world-class microclimate is somewhat of a coincidence—when the Mormons founded the city in 1847, the valley’s flat and settleable geography seemed to have been the main concern, with the Great Salt Lake just happening to be nearby. However, Salt Lake City has played a major role in building some of these ski areas up from unassuming hills to world-class destinations, with significant investments from city affiliates over the decades.

The big catalyst for many enhancements was the 2002 Olympics, which resulted in terrain expansions at Deer Valley and Snowbasin, arguably putting the latter on the true fly-to map, and coincided with substantial investments at Snowbird, Alta, and Park City as well.

Parts of Salt Lake City are just 15 or so minutes from the Wasatch Range ski resorts.

The northern Wasatch Range’s incredibly favorable conditions allow for eight destination ski resorts to exist within just one hour’s drive of one another.

Final Thoughts

So while Utah has earned its reputation for incredible mountains and world-class snow, the state is much more diverse than that, with areas that are just as flat and desertous as those that are mountainous and snowy. And while there are several mountain ranges across multiple expansive areas of the state, it turns out that only a segment of the Wasatch Range has the snowfall, prominence, and travel infrastructure necessary to support destination resorts. But at the same time, the Wasatch Range’s proximity to Salt Lake City and incredibly unique lake effect conditions not only support these destinations, but allow for eight of them to exist within just one hour’s drive of one another. All in all, ski resort suitability in Utah can best be described as feast or famine, and the Wasatch Range is definitely feasting.

For more information on skiing and snowboarding in the state of Utah, check out our comprehensive ski resort rankings for destinations in the state. If you’re interested in seeing how they compare to other similar mountains, check out our Rockies and overall rankings.

NOTE: The Utah maps used for this article were sourced from SANtosito on Wikimedia Commons, and edited with graphics on top of original work.